On a cold, snowy New Year’s Day, the workers and miners of a pair of Central Pennsylvania towns had a day to relax and enjoy the arrival of 1877. The residents of Lykens and Wiconisco were filled with hope for renewed prosperity in the new year. Mostly, they longed for an end to the financial crisis that slowed the progress of the American industrial revolution and a new influx in orders for anthracite coal.

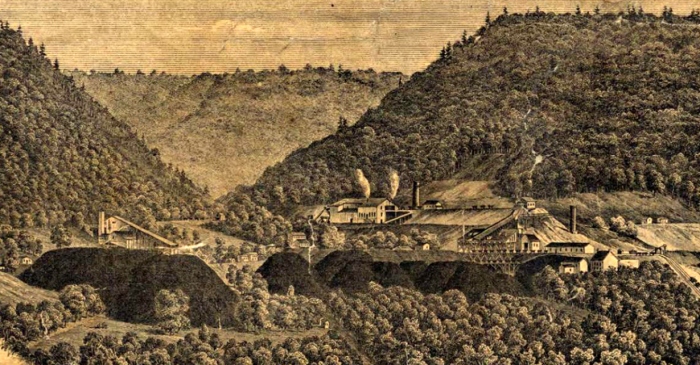

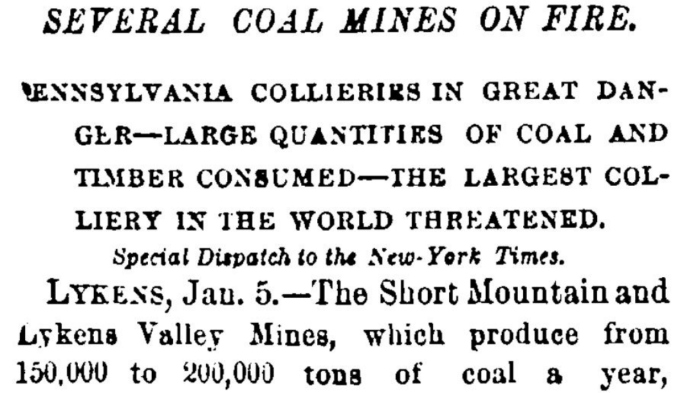

Above these twin communities stood the Short Mountain Colliery of the Lykens Valley Coal Company in Bear Gap. On this holiday, only essential personnel were at work within the miles of tunnels and gangways deep beneath the Pennsylvania soil. These were the engineers who ran the engines and pumps that ensured that the waters of Bear Creek did not flood out these valuable workings that sent nearly 150,000 tons of coal into market in 1876 alone.

Early in the morning, as the residents in the valley below stirred on January 1, 1877, an engineer inside the Short Mountain slope, on the western edge of Bear Gap, received a signal from above. He climbed to the Number 6 level, nearly one thousand feet below the surface. The engineer claimed that as he rode the lift to the next level, a spark from his lamp fell to the bottom of the slope, a few hundred feet farther down.

At the bottom of the slope lay “some dry wood or other inflammable matter.” The engineer testified that he believed this ignited when that spark landed there. Unaware of the conflagration that had just been ignited nearly 1,500 feet below ground, the skeleton crew working at the colliery that day went home to enjoy the day themselves.

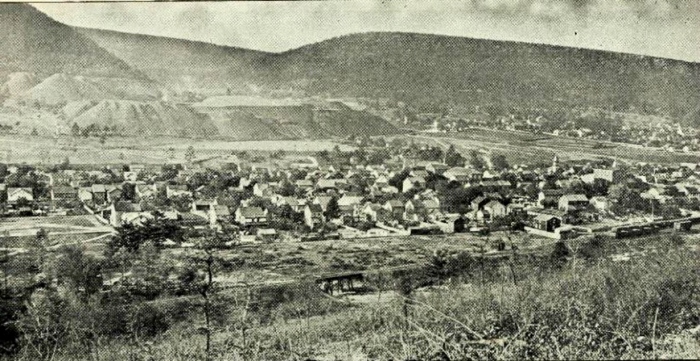

Communities up and down Williams Valley, a narrow basin running roughly east to west with the Wiconisco Creek at its center, relied almost solely on the prosperity of their interconnected web of anthracite coal mines. The collieries, as the combination of tunnels and outbuildings were called, all sat upon the northern side of the valley.

“Dependent on these collieries are the towns of Williamstown, Wiconisco, Lykens borough, and some two or three small villages, with a population numbering between 7 and 8 thousand [people],” recorded a state official in 1877. Most residents found some sort of employment either within the mines or in the supporting iron, metalworking, and engineering industries that the collieries found necessary.

“Eighty percent of the dwellings in this once prosperous valley, are the property of working men, the result of hard toil, self-denial, and privation,” noted the same official. They had been hit hard in 1876 by the continuing “Long Depression” that shook American institutions throughout the 1870s. In neighboring Schuylkill County, the economic turmoil fed ethnic disputes between Irish laborers and company ownership that fed into the “Molly Maguire” violence that shook the districts.

In Williams Valley’s communities, ethnic issues were less imperative than the workers’ rights. Brief strikes in the mines along the Dauphin and Schuylkill county lines had occurred occasionally since the middle of the American Civil War in 1863. Workers received occasional advances on their wages per ton of coal mined, but these privileges were often rescinded in hard times when work was slow.

Yet, on New Year’s Day 1877, prospects seemed bright. No one was yet aware that a fire had begun raging deep within the valuable colliery at Bear Gap.

Workers above ground were the first to realize there was a problem at about 2 o’clock on January 1. An immense steam whistle at the “Bull Engine,” a pump that lifted water out at a separate slope, blew a fire alarm down the mountain to the populations in Wiconisco and Lykens, and soon both towns were generally aware that something had gone terribly awry. Miners attempting to access the workings were forced to the surface by flames, fumes, and smoke.

“In eight hours… the fire spread with a velocity that covered 500 yards of shafting, filling at the same time the immense gallery diverging therefrom,” wrote a correspondent for the Harrisburg Daily Independent, a Dauphin County newspaper.

Workers attempting to extinguish the growing blaze ran into fire wherever they went. The Independent’s correspondent described their attempts at firefighting:

Contiguous to this mine, and connected with it is an old abandoned slope wherein more or less gas has always existed, which coming in contact with the flames of the first mine, has distributed the subterranean fire in every direction, even to the distance of two miles, forcing the suspension of operations and driving miners an laborers in horror from their work… The great object of those engaged in combating the flames is to keep them below the water level, and to do this the waters of Bear Creek, an adjoining stream, have been turned into the mine, but with very little apparent effect.

Smoke poured from the Short Mountain slope, which had previously brought clean, fresh air to miners at work below. Now it belched flame and toxic fumes. “Above this tremendous subterranean heat the earth is cracking and crumbling and falling into immense pits from which dense columns of sulphurous smoke issue,” a witness described.

The blaze jumped around the workings inside, following passageways from old workings and consuming everything in its path. Panic soon set-in among residents in Wiconisco and Lykens:

The general impression is among those who understand the topography of these mines that the fire cannot be extinguished; that it must rage until it has exhausted itself for want of fuel. So strong is this conviction among the people of the neighborhood that a panic exists, seizing men in their business transactions, and impelling them to the belief that their local interests have been swallowed up by the effects of the fire which is destroying the mines, as all business there of an individual or general character, merchandizing and manufacturing, is made dependent on the mining interest.

The next day, January 2, desperate authorities at the Lykens mines sent for the assistance of Harrisburg firefighters. Within a day’s time the Paxton Steam Engine of Harrisburg had arrived to help squelch the inferno.

For the miners and volunteer firemen from neighboring communities fighting the fire, the blaze below must have seemed a confusing monster. Each time they believed they were making progress, the fire appeared elsewhere and the prospects for saving the colliery and its invaluable supply of coal seemed to sink. As they poured the waters of Bear Creek down the Short Mountain slope on January 2 and 3, the fire suddenly appeared behind them and consumed the engine house holding the “Bull,” which had sounded the alarm on January 1.

Initially, fears for the entire Williams Valley mining industry were heard from the bosses and miners alike. The mines at Wiconisco were connected via underground tunnels with Big Lick and Williamstown Colliery three miles to the east. However, these fears were squelched when miners from Big Lick trekked those three miles underground to gauge the damage and to make an attempt at saving the mules who were still in their stables beneath Bear Gap. They were removed safely from their underground stables several days after the fire began. Those that made the journey from Big Lick confirmed that fire had stopped spreading to the east.

Firefighting operations at Short Mountain were described by area newspapers:

Lykens Register (January 5)

At noon today (Friday) there is a strong force of men at work at Lykens Valley slope. Water is being conveyed through a column of pump pipes near the slope, to the bottom of which, or nearly so, a hose is attached for attacking the fire, which has broken into and is burning on the west of slope, about 70 or 80 yards below the surface…

Harrisburg Independent (January 6)

The fire in the mine is still burning. The Paxton fire engine is working hard. They built a small house with sufficient means to keep the engine warm, and from freezing, by stoves. The Paxton boys do not altogether like the freezing and disagreeable accommodations. When they arrived here it was near dark, and notwithstanding the cold and snowy weather they went to the mine at once. Having no house to put their engine in they had to go back to Lykens.

Then their pipes froze and burst. They are now pumping water down the Lykens Valley slope into an eleven inch pipe from their hose from which men are playing water on the fire. They have changed the air so as to drive the air all towards the pipes, and are following it up. They gained a distance of about 30 or 40 yards yesterday. The slope is down 480 yards from the surface. The fire first started in the bottom of the water course, which is also 480 yards from the surface from which they pump out the water…

All the creeks and water around the place is now being run down the mines and all is [decided] that no more buildings will burn. Breaks in the slope have and will still occur, which must be replaced, and will result advantageously to the laborers who number about 150 to 200 men are working at times. We had fires here before and they were put out. So will this fire be extinguished.

The fight against the flames went on for six weeks, with regular progress checks published in area newspapers. Panic receded as the flames were checked and the fire drowned under the waters of Bear Creek. The Lykens Record put the estimates of damage and lost revenue at nearly $1 million. On March 2, 1877, officials declared the fire extinguished. Recovery work began shortly afterward.

Over the course of the fire, not a single life had been lost, a fact universally held up as the only bright mark of the whole event.

Yet, when the community looked at what was lost and the hard times still to come, it hardly seemed believable. Millions of gallons of water had been deliberately pumped into the Short Mountain Colliery. If work was to resume for the nearly 800 men employed in these mines, all that water had to be pumped back out. That grueling work officially began on May 5, 1877.

From the Lykens Register:

The order to pump the water out and fit up the mines for business was received by Superintendent Hanna, on Saturday last, who at once set about its execution. Proposals were issued on Monday morning for opening and retimbering Short Mountain slope, from the top to the old level, the contract for which was given out last week. The work is to be pushed night and day until completed, and will give employment to about 40 men.

Various estimates are placed of the time required to take out the water. It is reasonably certain, however, that no coal can be shipped before some time next fall. The following figures will give the reader an idea of the quantity of water hoisted in a single day with the present facilities, and an additional pump will be put to work in a few days: Bull pump at 180 gallons a stroke, 4.5 strokes a minute – in a day, 1,166,400 gallons

Two water wagons – every three minutes, 1093 gallons; in a day, 338,830 gallons

With great fanfare, the last of the water used to flood the mines in January 1877 was pumped out on Friday, November 9, 1877. “[T]he event was duly celebrated on Saturday, by general festivities among the bosses, workmen and citizens,” wrote the Lykens correspondent at the Harrisburg Independent.

Ahead of schedule, the Short Mountain Colliery shipped its first coal in more than a year in March 1878.

This fire received great attention throughout the country when it broke out in 1877. Today, it has largely been forgotten. The fire nearly wiped out the economy of this region of Central Pennsylvania, first threatening it with fire, and later with water. Paired with a devastating economic recession, the results were tragic. While no lives were lost in the course of this disaster, a terrible human tragedy developed.

From one small spark in the depths of a coal mine, thousands of lives were to be forever altered.

Featured Image: The Short Mountain Slope in Wiconisco Township

Great article and very informative talk at the Lykens Historical Society. I enjoyed your emphasis on the impact on the Lykens community. The long lasting effects of this catastrophe extended into the turn of the century. The fire brought out the good as well as the bad of our human nature. Thank you for this presentation.

Best Regards,

Jim & Pat Leaman

LikeLiked by 3 people

Not much sense in me posting a new comment saying almost the same words. My 2nd Great Grandparents and sons were miners up there at the time and I presumed they worked in that mine. I had seen a few of the clippings before, but this is the first time to hear or read the expanded story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I grew up in Lykens. First time I heard this story. I remember going to the burning banks to shot bb’sintobeer cans

LikeLike

i enjoyed your article i am formerly from hat region i was a Schoffstall and my grandfather Forrest Schoffstall suffered from black lung from working in the mines, i .am intrested in hearing more history

LikeLike